50 Years After Jaws: A New Appreciation for Sharks

This year marks half a century since the premiere of Jaws, the summer blockbuster that's sent a chill down the spine of any swimmer who's ever had a piece of seaweed unexpectedly brush their leg.

The infamous star of the movie, of course, is the monster great white shark "Bruce" (a moniker given to the animatronic shark prop by the movie's crew), who terrorizes vacationers in the fictional beach town of Amity Island. In the film, Bruce is made out to be an indiscriminate, people-hunting, awe-inspiring predator. In the real world, only that final descriptor is true.

Fighting A Bad Rap

In the decades since Jaws, sharks have endured a tarnished reputation, with even Peter Benchley (author of the novel that inspired Jaws) and director Steven Spielberg expressing regret with the negative effects that the film has had on the shark's public image and conservation. That reputation hasn't been helped by the hundreds of other films and television programs that have played up sharks as cold-blooded killers, either. (No, Sharknado doesn't count.)

As a result, sharks have been killed in great numbers, both intentionally (for their fins or out of fear) and unintentionally (as bycatch in fishing nets). Unfortunately for sharks, which tend to reproduce slowly, they are struggling to keep up their population.

The over 500 extant species of sharks are vital to their respective ecosystems, from reefs, to coastal inlets, to the open ocean. And like wolves in Yellowstone National Park, sharks help to keep the populations of their prey items in check, contributing to the overall health of the ecosystem.

- Learn more about the shark's important role in ocean ecosystems in the video "Sharks, Rays, and Coral Secrets" by N*Gen.

Sharks Have History

Sharks have been around for a long time, as far as the timeline of life on Earth is concerned. But they're not just old—they're old. We're talking "before trees" old: the earliest fossil evidence of a shark ancestor has been dated to approximately 420 million years ago. To put that in perspective, trees began to sprout up around 380 million years ago, the first dinosaurs walked the Earth around 250 million years ago, and the earliest human cropped up only a measly 3–4 million years ago.

All this to say: Sharks have had millennia to become the fine-tuned animals that they are today, and they've evolved to be durable, deadly, and worthy of admiration.

No Bones About It

Sharks are cartilaginous fish, which means that they have skeletons made of cartilage—similar to what makes up our ears and noses. The resulting flexibility and elasticity of the shark's spine, along with their efficiently shaped bodies and caudal (tail) fins, allow sharks to rapidly move their bodies from side to side, propelling themselves forward quickly and efficiently as true swimming machines. That's critical for predators who who need to strike hard and fast, often in ambush of fast-swimming prey.

Teeth From Head to Tail

Now, we know what you're thinking: "If sharks have no bones, how could we have fossil evidence of them from millions of years ago?" The answer is teeth!

Shark teeth, like our own, contain minerals and can become fossilized over time—a process called permineralization. Cartilage, on the other hand, breaks down much more quickly. Plus, sharks are constantly losing and producing new teeth, and have several rows of teeth lying in wait behind their active set, as pictured above. When one falls out, a new tooth moves up to replace it.

- Explore the importance of traditional Hawaiian shark-toothed weapons in this teaching guide from Science Friday Initiative.

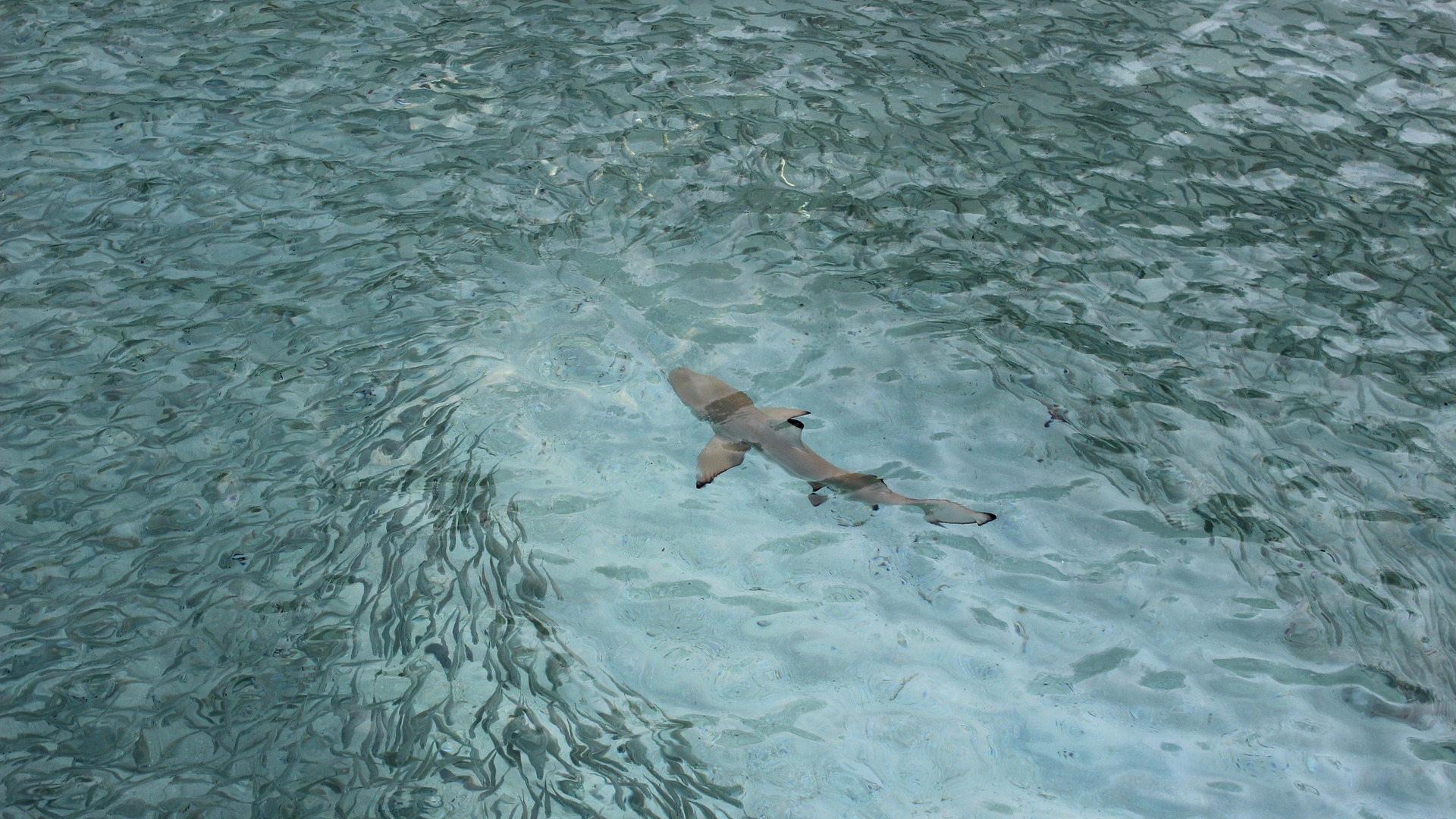

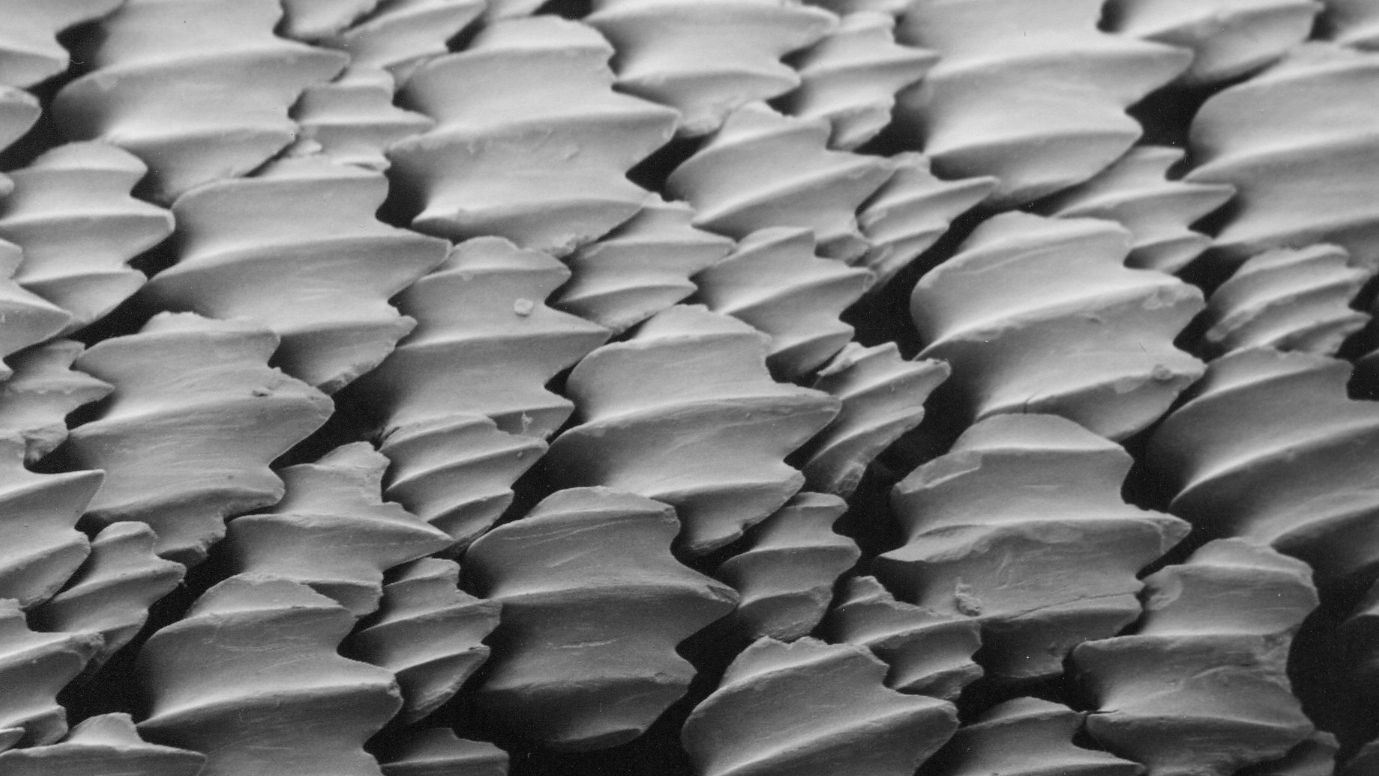

In addition, sharks have a very unique type of skin. Instead of usual fish scales, shark skin is covered in millions of microscopic structures called dermal denticles, which are more similar to teeth in shape and appearance. They are mineralized and covered in an enamel-like substance, like teeth, and they all face one direction, aiding in the shark's aerodynamics as it swims through the water. If you've ever felt the skin of rays (a relative of sharks) in an aquarium touch tank, you may have observed that it was smooth in one direction and rough in the other. That's thanks to dermal denticles!

These are just a few of the many fascinating things to know about sharks. Learn more about these important animals from our collaborator Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, whose fantastic learning resources about sharks and ocean conservation can be found in the LabXchange library.

Shark Conservation: An Interview With Temba Mettler from Justice 4 Jaws

At LabXchange, we work with countless skilled people with diverse interests. One such person is Temba Mettler, senior instructional technologist at Learning Sandbox, who volunteers his free time working with Justice 4 Jaws, a non profit dedicated to shark conservation in South Africa. We spoke to Temba to learn a bit more about the organization and their ongoing efforts to change the shark's much-maligned image.

What is your involvement with Justice 4 Jaws, and what does the organization do?

I am currently the Chairperson of Justice 4 Jaws (J4J) and have been for the last 2 years. J4J is a non-profit company that is funded by the WILDTRUST to create awareness and educate people about sharks, skates and rays, with the hope of inspiring some people into actively protecting them. We engage with people through online and/or in-person workshops, webinars, talks and any events that promote marine conservation.

Most recently, I represented Justice 4 Jaws at the Plett Ocean Festival in South Africa where we played ecologically-themed games with a range of 25 to 40 children each day for three days.

What inspired you to get involved in shark conservation?

Initially, I joined J4J because some university friends started the group and needed someone with work experience to advise on internal processes and conflict management. As I spent more time in J4J, as it developed into a real NPC and as I participated in more activities, my appreciation for the work grew.

The real pivotal moment was when I attended the Shark & Ray Symposium in 2023. Four or five days of listening to scientists, environmental managers, students and others opened my eyes to the vastness of the shark conservation sphere. I also love science and could listen to people talk about their research all day long. Ultimately, being in J4J inspired me to engage with shark conservation.

What is the main threat that sharks face currently?

Currently, the greatest threat to shark numbers is commercial fishing. Sharks are consistently caught as bycatch when fishing vessels target fish and other marine life. By the time a shark is pulled out of the net, it is likely already dead. Sharks are also targeted in fishing related to the production of shark-fin soup or other shark-based delicacies.

Although it's less tangible, fear is another threat sharks must face. When people are scared of sharks, they are less likely to engage with their struggles and form one collective voice to ensure nation-wide change. So, fishing and fear are the biggest threats sharks face.

In your opinion, what is the biggest misconception that people have about sharks?

In my opinion, the biggest misconception is that sharks eat people and that they will eat you if given the chance. If you think about the news articles you've read on shark bites, you'll notice that while people get bitten, there aren't stories of people being eaten. Sharks can only verify whether something is food by touching it with their snout or by biting it. Sharks also spend more time close-by at the beach than what people realize.

What is your favorite fun fact about white sharks, or sharks in general?

My favourite shark fact is that they can eject their stomach from their mouth to clean it. The process is called "gastric eversion" and it's an ability that they share with some frogs.

What can the average person do to help shark conservation?

For those of us scared of sharks, learning about them is the best way to support their conservation. Besides that, spreading the word that sharks are not "out to get us" is very helpful to their conservation.

.svg)

.svg)